Introduced by Foucault late in his career, during the lectures at the College de France, governmentality spawns perhaps the most discussion among contemporary readings of his works. And no wonder:

Foucault takes a great deal of time and effort to outline the concept, including in these works:

- “Society Must Be Defended” (1975-1976)

- Security, Territory, Population: (1978)

- The Birth of Biopolitics (1979)

- The Government of Self and Others (1983 )

- The Courage of Truth: (Government of Self and Others II)

- from Power/Knowledge: “Two Lectures”

- ” Politics and the Study of Discourse”

- “Omnes et Singulatim” – lecture at Stanford

Distinct from, yet in close relation to, biopower and biopolitics (a topic discussed in the next essay here), governmentality undergoes a shifting set of definitions, but Foucault eventually settles on a broad, complex working one. Paraphrased:

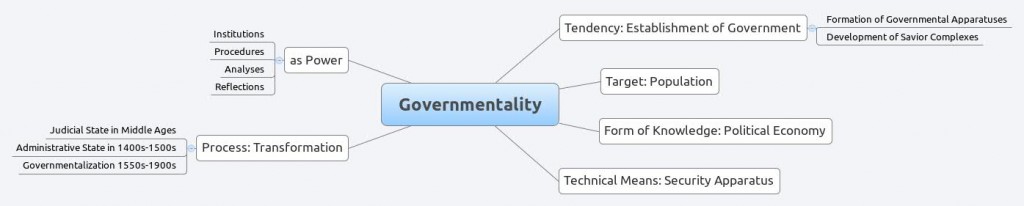

1. The ensemble formed by the institutions, procedures, analyses and reflections, the calculations and tactics that allow the exercise of this very specific albeit complex form of power, which has as its target population, as its principal form of knowledge political economy, and as its essential technical means apparatuses of security.

2. The tendency which, over a long period and throughout the West, has steadily led towards the pre-eminence over all other forms (sovereignty, discipline, etc) of this type of power which may be termed government, resulting, on the one hand, in formation of a whole series of specific governmental apparatuses, and, on the other, in the development of a whole complex of saviors.

3. The process, or rather the result of the process, through which the state of justice of the Middle Ages, transformed into the administrative state during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, gradually becomes ‘governmentalized’.

(Burchell, Gordon and Miller, 1991: 102-103)

Diagrammed:

This map to be superceded by a more complete one detailing different modes of power in Foucault. See Position essay here.

The definition raises three problems worth investigating – schematically here, and later, in greater detail as against the deployment of the concept by contemporary readers of Foucault. First, we face the historical point of emergence of governmentality so long ago that its explanatory claims extend towards universality, at least if the European context of the framework is assumed and not interrogated. Second, the concept’s distinctions from and relation to biopower form a larger, more complex structure than either – a broader mapping of the development of power relations as such in contemporary society. Third, the roots of the forms of knowledge made explicit through a recognition of governmentality paradoxically grant governmentality explanatory power over the totalizing tendencies of governmental apparatuses because of their combination of archaeology and genealogy as opposed to other less complicated methods of analysis.

On the question of when and how governmentality emerges as an observable, interpretable phenomenon, Foucault points to the transformation of existing systems such as juridical and administrative state apparatuses. The consolidating tendency of governmentality, though, as mapped historically by Foucault through archival materials that show the introduction of more complex, more numerous institutions and regulations of the population over the course of European history, conflicts with the simultaneous tendency of power relations to multiply and proliferate across a variety of such institutions, not necessarily binding the latter together but sometimes holding them separately. Meanwhile, the tension between consolidation and multiplication of power relations also brings about the rhetoric of self, family, community, and state that undergirds the further need for more complex state institutions, and a more technically adept security structure. In this way, the same forces that drive governmentality to continually include the bodies and lives of those needing salvation among its populations drive it to develop repressive or exclusionary mechanisms by which to control those populations.

It is here that we see the critical ties between governmentality and biopower. The differences come first: biopower remains a firmly historicized notion of the administration of biological life, deployed with the goals of optimizing and multiplying that life. Meanwhile, biopower’s provision of the conditions under which governmentality can flourish keeps it at a slight remove in the terms of analysis here. For example, while biopower helps explain how governmentality operates on and through historically marked bodies, it does not explain the longer-term formations of governmentality or biopolitics, for example, neoliberalism or globalization as we speak of them today. Instead, the connections between the three should be seen as meta-systemic: biopower operates in historically concrete situations through processes of governmentality; governmentality’s expression requires biopower but the specific development of biopower also necessitates a unique form of biopolitics. Biopolitics, which does not equate to either biopower or governmentality, will be explored in a separate essay here, and in more depth down the line. What the juncture between power and knowledge expressed by governmentality leads us towards is a means of analyzing the whole set of relations as a complex, but coherent, system.

To that end, consider the instrumental deployment of methodological impulses that Foucault exercises in different iterations of his analysis of governmentality. Importantly, he focuses on what he calls local, or subjugated knowledges, as the object of that analysis. The articulation of local knowledges as opposed to systemic formations leads to a hybrid of the approaches that he has spent so much intellectual effort to outline in his longer books. Archaeology takes on the role of a research method in the governmentality project, in order to reveal those local knowledges. Then, genealogy comprises the tactics by which that knowledge, once revealed, is deployed in contrast to dominant forms of knowledge, such as the political economy that buoys governmentality’s own epistemological constructs.

In this way, Foucault approaches the problems of governmentality with a mind to their inversion into non-totalitarian solutions to those problems. The implementation of those solutions, as ever, is beyond the realm of critique, however pointed. Instead, he focuses on the development of a course of political action, one which he would himself undergo in his involvement with the Prison Information Group and in support of the Iranian revolution. Those events will require separate consideration, of a more biographical nature, than the conceptual engagement proposed by these posts.

How should your diagram be cited?

Hi,

Glad to see that it is of interest, hope it’s useful. You could probably just cite the URL of the image itself.

Lewis, this piece has been incredibly helpful for me. Thank you.

I’m so glad to hear that, thank you for letting me know.

Hi, Its a very interesting piece of work. How should this work be cited?

Hi,

Glad to see it is of interest. I would advise citing this page as a web page, in whatever citation style you use.