Category Archives: academic

Foucault – Tutor-Texts and Intellectual Lineage

This first post in a short-term regular series of essays on Michel Foucault deals with his most famous influences. I begin with the precursors to Foucault’s own production of knowledge because their work and tutelage form the conditions of that production. This requires that I oversimplify some of their contributions to cultural scholarship and critical theory. I hope to maintain a baseline level of respect for their importance without fetishizing their names, just as I intend to maintain the tension between the familiarity of Foucault’s own name and the irreducibility of his intellectual production to any single certain thought or text. Enough lingering on qualifications and breast-beating, then. Let me turn to the names and their significance for Foucault’s emergence as a theoretical producer – and event.

- Michel Foucault – image via Creative Commons.

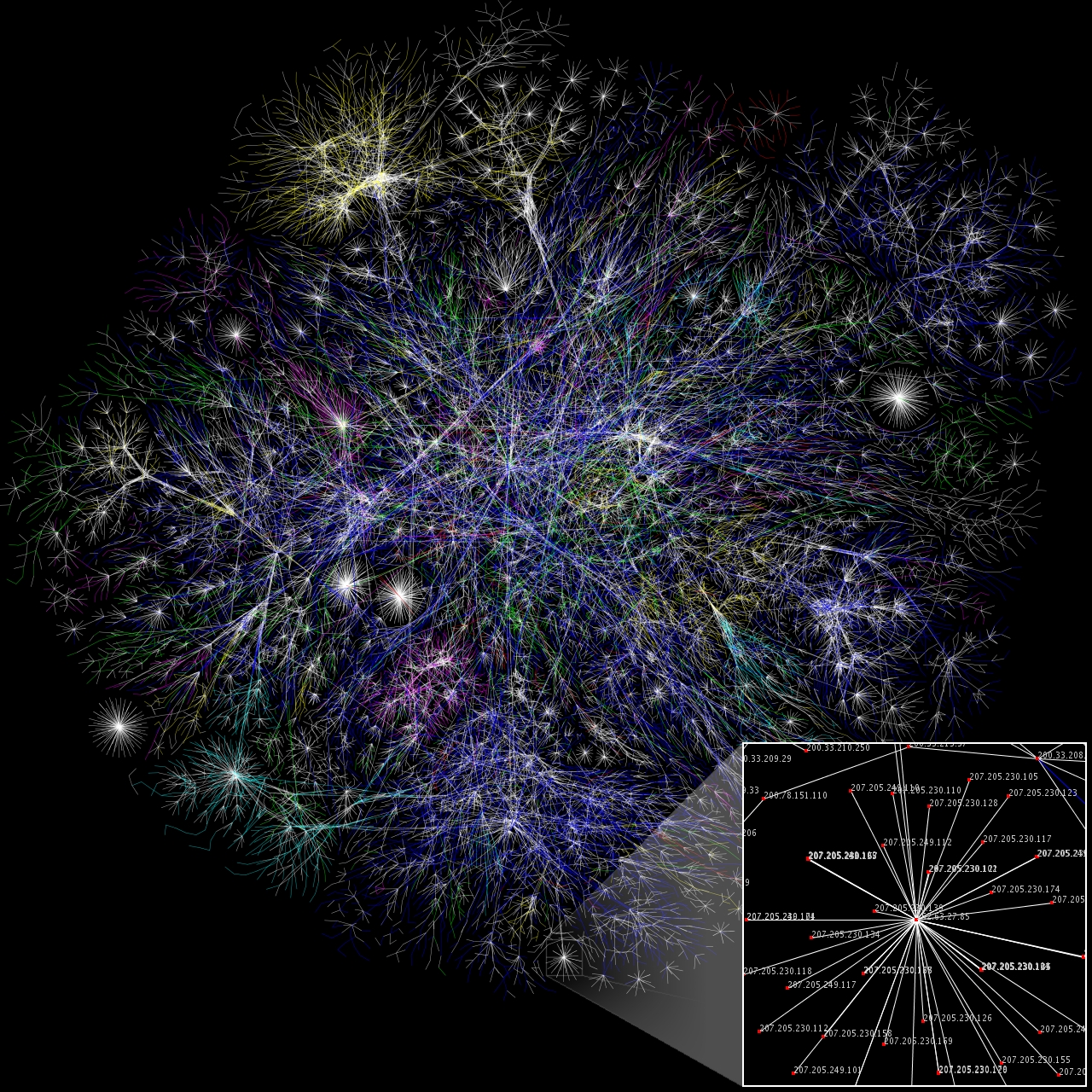

Internet – Introduction

For all its familiarity to users on a daily basis, the internet remains a strange and wild beast, full of secrets and surprises for those of us who take it as our object of research. This marks the first entry in a weekly series of short essays, reflecting on my independent reading this semester with Dr. Sharon Leon, on the topic of the internet in cultural perspective. This week, I will lay out the key terms, concepts, and questions for our course of study, and note the work plan for the semester by way of conclusion. Over this semester, I hope to learn not only myriad technical details and interesting anecdotes about the internet, but also how a rigorously cultural approach to its study might inform my own and others’ future research. These essays should serve to keep the research regular, progressive, and grounded: the best technique that I know for tackling large and complex problems is patience and determination.

For this week, I reviewed some technical literature on the definition, statistical character, and high-level architecture of the internet. These came from academic, market research, and non-profit sources. The wealth of data available now – an archive stretching back at least through the early 1990s – provides some clear background. The internet today comprises some dozen layers from physical infrastructure through end users, and encompasses some untold trillions of web pages, links, and networks. Of course, the most important key terms that this week’s readings reinforced were the obvious ones:

- Networks – the baseline units of which the internet is made up. Comprised of public and private, virtual and physical, metaphorical and concrete, networks are the touchstone and the cornerstone of both the idea and the artifact of the internet. We define networks for our purposes as sets of connected agents – machine, human, or virtual – and include in the set the connections themselves.

- Communication – When we define the internet, we encounter conflicts between those (e.g. the FCC) who wish to define it as a communications medium akin to telephony or broadcast television, and those who seek another primary definition (e.g. the FTC, who wishes to define it as a commerce and trade platform like the stock market, or others who believe that it constitutes a public utility like the power grid or water supply lines). For our purposes, we can remain comfortable with a complex and often contradictory definition that accounts for different structural, economic, and cultural deployments of the internet. This is because we will define it primarily as a CONCEPT, and only secondarily as an ARTIFACT.

- Medium/Media – Regardless of the legal or formal definition of the internet, its status as a communications medium is hardly in doubt. In practice “new media” has folded largely into the internet – digital communications, human-computer interaction, and computer-mediated-communication included alongside applications such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, email, and the like. We use media in the broadest possible sense, then, following McLuhan’s prescient if aphoristic sensibility most of the time.

- Structure and Infrastructure – The first few weeks of this course will dedicate their time to unpacking and making clear the incredible complexity at work in the background of any internet instance. The most important aspects of structure and infrastructure, from a beginner’s standpoint, are layers, links, protocols, platforms applications, and services. We will define these in more detail next week.

- Other terms to be defined next week: community, commodity, and architecture.

The key questions for this week are the overall questions for the course. When we define “the internet,” two specific parts of that definition resonate for our purposes. First, what is unique about the internet as a cultural object? Second, what does a cultural study of the internet entail? These lead to our historical inquiries: how did the internet as we know it develop, what kinds of labor were involved, and how has its cultural significance changed over time? We also encounter architectural questions of culture: who maintains and manages each layer, who composes and follows each protocol, and to what ends? Placing the object in social and political context, we will ask whose interests the internet has and continues to serve, and what the mutual effects are between its structure and its context. Finally, diving into the questions of cultural significance, we will examine the internet’s political, economic, and subjective impacts – or at least plan how to answer those. For the next week, however, we will focus on a specific question: What is the structure of the internet? By the time we ask how it got that way, we will have entered the historical aspects of our investigation.

- This is perhaps the most popular visualization of the internet.

PIC Conference Roundup

The organizers of the Philosophy, Interpretation, and Culture conference put together a phenomenal roster, worth rising at 530 and riding two hours (luckily, as a drowsy passenger riddled with illness) to attend. The overall themes, time and revolution, lent themselves to radical and stimulating interpretation. Harpur College Dean Donald Nieman’s speech praised PIC’s interdisciplinarity and its outstanding reputation, hitting the mark on both counts, but underscoring the ironic troubles facing the program. To that point, great credit goes to Scu and Cecile for their elegant and rigorous work putting the whole thing together in the midst of this crisis.

My paper came first for the first day, and just a few minutes in, the room had settled into the patient quietude of academics parsing an argument about research on cultural theory. The Dean left early on, but about forty people were already gathered for the conference proper, and I delivered my thoughts alongside Brad Kaye‘s provocative paper, which framed a potential mass refusal of work by “disabled and mad” laborers in terms of Negri’s theory and the dark example of Bartleby the Scrivener. His drew many more questions than mine, but when our panel wrapped up, I was able to relax while speaker after speaker delivered high-quality theory and research.

Just about every panel seemed ideally constituted, with concepts and methods playing off of one another in provocative and inspiring ways. The next panel’s juxtaposition of Natalie Churn’s paper on Australian “bogans” with Joanna Grim‘s explanation of and reading from her one-act play “Dawning of Time” illustrated the diversity and creativity that would shine through the rest of the conference. Often, the creative interventions complemented and highlighted their panels’ themes in unexpected ways. For example, Brianna Hersey’s slam-style performance/paper that recounted her personal narrative to argue for an ontologically unstable “queer sick time” set the other papers in that panel on “embodied time” into sharp relief. These included Fanny Söderback‘s work on Kristeva, Grace Hunt’s compelling reading of Susan Brison, and Carolyn Culbertson‘s painstaking comparative approach to Derrida and Kristeva. The following panel combined Rosa Barotsi’s explanation of the revolutionary potential of cinematic slowness, Ross Birdwise‘s video/audio artist, Craig MacKie’s resuscitation the marvelously obscure Henry Darger, and a fabulous explication of the necessity of thinking ecological politics in a framework of ‘deep time.’ The latter, presented by Ben Woodard, would be a great fit at the Cultural Studies conference in the fall.

Peter Gratton‘s keynote speech also broached the question of ecology, though from a somewhat opposite tack. He argued that since politics reduces to time, time becomes the necessary precondition of politics. Taking the standpoint of a certain realism, he posited a “temporalism” of philosophy. From there, he posited a “partage” of many temporalities of reality, and conversely, of the reality of a democratic partage, along with a temporal reality that indicates a partage of time. All this led him to call for a contingent, speculative, and realist “ecology of times” as the grounds for political thought.

By the end of the first day, my illness had overwhelmed me, and I retired to the apartment rather than hanging out with the other conference attendees. That rest served me well, though, the next morning, when a whole new round of challenging ideas came rushing through the second day of the conference.

A panel on epistemology, revolution, and time included two papers on Benjamin by Sylwia Chrostowska and Miles Hentrup, one on the concept of kairos as the time of revolution by Rowan Tepper, and a fascinating rebuttal of a Lacanian turn in Laclau by Javier Burdman. The following panel included yet another Benjamin paper, this one by Christian Garland, as well as another Derrida paper by Chelsea Harry, and the first social media paper, by Kamilla Pietrzyk. The three meshed surprisingly well, and the discussion that followed the presentations was the best-rounded and perhaps one of the liveliest of the day. After this, we got a treat of a panel that included Rochelle Green’s excellent reading of Bloch’s concept of nostalgia, David Kishik‘s “meditations” on Agamben, and Netta Yerushalmy‘s presentation of a dance performance. By this time, my brain was on fire, but that might have had as much to do with illness and its medications as with concepts and their presentations.

Another fabulously well-constituted panel followed. It combined a provocation and research plan from Matt Applegate, on the Manifesto as such, with a reading of Bataille that countered Agamben’s interpretation of Bataille’s concept of sovereignty by Tommaso Tuppini, with one last Benjamin paper, delivered with aplomb by Antoine Chollet. The next panel, on political theology, took a different turn.Devin Shaw delivered the only other reading of Schmitt of the conference than mine, and the antagonism to Spinoza that Shaw set up has sparked more than a few questions in my mind. Daniel Barber compared Negri and Agamben, two tricky figures in political thought, by thinking their uses of the Figure as theological signifiers. Graham Baker unpacked Kierkegaard’s politics of the apocalypse for us. Finally, an undergraduate from Texas, Cameron Vaziri, detailed Foucault’s search for a new concept of revolution via involvement with the Iranian revolution of the 1970s. By the time the final panel came around, the crowd had thinned out. Because of that, they missed perhaps the most challenging lineup of papers of the conference. Three of the four dealt with Deleuze, and the one that didn’t read Nietzsche. As a humanist, no less – Jordan Batson framed Nietzsche’s grounding of History as a human science in terms of its methodological requirement for a telos of Life. The Deleuze papers included Allison Merrick’s treatment of the differences between Deleuze’s concept of “becoming” and a concept of “history” as such. This was followed by Bryan Nelson’s complementary argument that “becoming-democratic” for Deleuze always situates actually existing democracy, and perhaps even politics as such, in an unpresentable future. Finally, Anupa Batra presented an excellent, patient explication of the unique and problematic temporality of Deleuze’s “becoming-woman.”

Immediately after the last panel, I had to leave. I regret that, because of this, I couldn’t have spent a little more time just talking with some of these brilliant and assiduous scholars and artists. Hopefully, as I begin to catch up on their various blogs and publications, they’ll all appear in the conferences and venues that link us across institutions, geography, and disciplines. I’ll consider coming into contact with them again a great privilege.

prezi

thesis statement

I study the recordings, writings, and public figure of Mumia Abu-Jamal, a Pennsylvania death-row prisoner since 1982. I analyze synecdochic manifestations of his body in space, his oeuvre in time, and the codes of his figure online. This includes examining analog and digital media artifacts, as well as observing figurative representations of both Abu-Jamal and Daniel Faulkner, the police officer that Abu-Jamal is convicted of killing. I use interdisciplinary theoretical and methodological interventions to show how the social and political implications of this polarizing narrative extend beyond either man’s life or death.

new thesis statement

I am studying the cultural production of Mumia Abu-Jamal, a prisoner in Pennsylvania and a prolific writer. Cultural production has two senses here; first, it refers to the cultural artifacts, such as writings and audio recordings, produced by Abu-Jamal while incarcerated since the early 1980s. Second, it refers to the many ways in which Abu-Jamal has been produced as a cultural icon for certain political causes, especially online. Combining theoretical constructs from critical literary studies, communication, cultural history, and media studies, I examine production and its limits, across the media of print, radio, and the internet.

Also, I made a page on my CCT portfolio to house (and back up) my work over the spring.

thesis lit review draft 0.5

lit review – draft, includes working annotated bibliography. download as PDF

recently completed

presentations on Foucault, stitched together via MERLOT

another thesis statement

I am studying the work of Mumia Abu-Jamal, a journalist, activist, and death row inmate. I want to find out how it has been censored in three different mediations: in print, on the radio, and online. I am interested in what the conditions of censorship were for each of those forms. Since these conditions include interpersonal, systematic, and internalized practices, I hope to show my reader that censorship is a complex system, with technological and social factors. This means that a change in one part of this system can have profound effects on the structure of social relations at large.