The ethical position taken by academics and intellectuals with respect to the objects of their attention – research, theory, intervention – arises from a combination of environmental, institutional, and personal (i.e. political) commitments. When those commitments come into conflict, the ethical positions taken or implied by knowledge producers face the possibility of transformation. And, where globally interconnected lives at both macro- and micro-scopic levels are concerned, the conditions of possibility of change are omnipresent and intense. Arjun Appadurai (2000) summarizes the root of these conditions as a “growing disjuncture between the knowledge of globalization and the globalization of knowledge.”

Continue reading

Tag Archives: flows

The Plan

Internet – Synthesis – On Newness

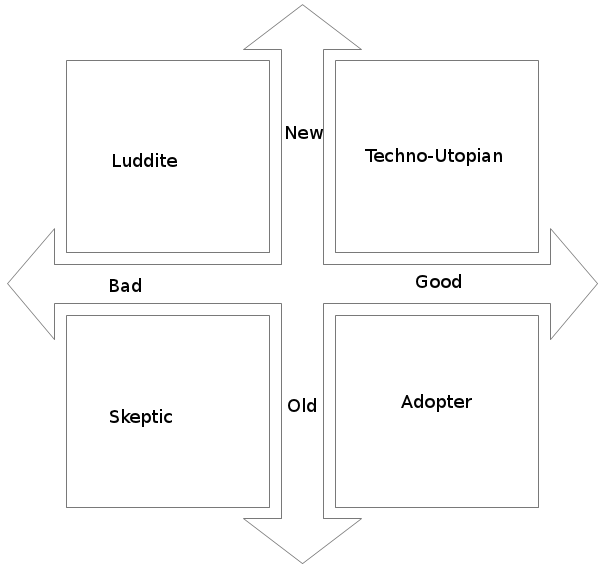

The question of what, after all, is so new about the internet has run through the introductory and summary posts in this series. It is a divisive question. Some proclaim the revolutionary, worldchanging emergence of the internet a wholly unique phenomenon. Others describe its continuity with older forms of media, communication, technology, or ideas. And each vein has its proponents and detractors of the internet’s cultural effects, which seem ubiquitously manifest, though not unequivocally ethically or morally valenced. Since we are concerned, here, with not just cultural effects but also cultural conditions for today’s internet, though, we cannot neatly reduce our approach to any of these positions.

So, we are faced with a series of comparisons and contrasts.

Internet – Geography, and Africa Introduced

We expect no clean equivalence between infrastructure, labor, capital, and internet development. Still, we know that the growth of a robust modern internet takes vast amounts of time, skilled labor, and knowledge — all elements of advanced capital. So, when we consider the rise of today’s African internet, we must ask, first, who builds it — and then, where its infrastructure overlaps or clashes with existing geographical patterns. Heavily visual organization and logic help think through these issues of backbone, traffic, and investment. Their combination leads to some interesting insight to the specific challenges facing the continuation of Africa’s internet-building. Continue reading