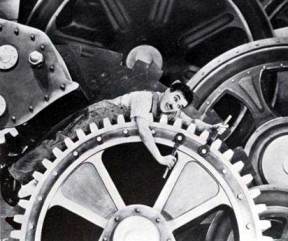

At a relaxed dinner with a good friend recently, we discussed the difficulty of finding a job in Detroit over the last few years. We spoke about the population’s available, marketable skills, and compared the price of land/rent to the type of organizations with the capital to buy it up. Then, we touched on a curious potential outcome of the current grim circumstances. In ten or fifteen years, we posited, when the city has grown again and its workforce is active again, a primary economic driver could well be the Silicone titans. This unusual placement of internet-driven internet drivers would seem out of place in the Motor City, except for a few key factors. First, technology industries require massive investments of capital for infrastructure and of labor for support in addition to the engineers and designers who are their most visible participants. Second, the data in the United States flows through Detroit, necessitating more of those support staff as that stream grows. And finally, the low cost of land and utilities, and the propensity of large IT firms to model their operations on 19th and 20th century factories, means that the companies have incentive to move to such an area already. Some small moves in this direction could trigger large changes to the economic situation there. Continue reading

Category Archives: Internet Studies

Weekly responses to issues in internet infrastructure, culture, society, strategy, policy, and theory.

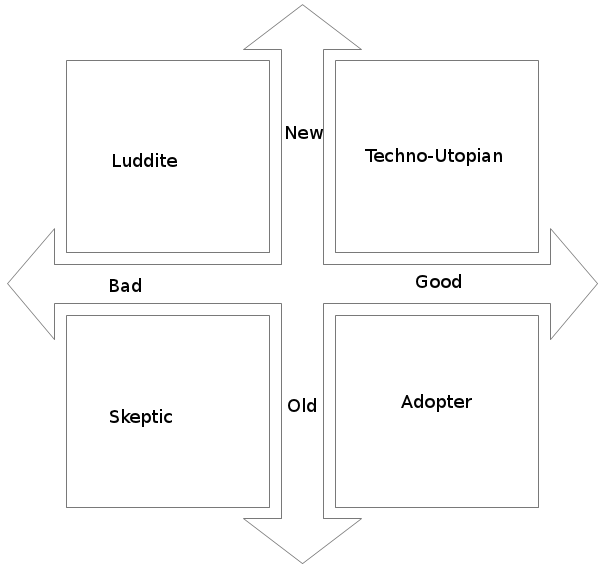

Internet – Synthesis – On Newness

The question of what, after all, is so new about the internet has run through the introductory and summary posts in this series. It is a divisive question. Some proclaim the revolutionary, worldchanging emergence of the internet a wholly unique phenomenon. Others describe its continuity with older forms of media, communication, technology, or ideas. And each vein has its proponents and detractors of the internet’s cultural effects, which seem ubiquitously manifest, though not unequivocally ethically or morally valenced. Since we are concerned, here, with not just cultural effects but also cultural conditions for today’s internet, though, we cannot neatly reduce our approach to any of these positions.

So, we are faced with a series of comparisons and contrasts.

On Google’s Privacy Policy

Effective 1 March 2012, Google adjusted the terms of its privacy policy, affecting users of all its applications. There was no option to waive or deny these changes, aside from cancelling one’s accounts, which would still require the migration and/or deletion of emails, documents, and personally identifying information from Google’s servers. Further, the policy became homogenous across every service and product that Google offers. These were not unprecedented changes, as many End User License Agreements and other similar contracts assume that use of a product or service constitutes unmitigated acceptance of the provider’s terms. But this round of legalese brings two unique changes to discussions of privacy and openness. Ongoing lawsuits against Google (among other large technology providers) highlight the stakes of thses discussions. Many of us are so deeply invested in the daily use of Google’s products and services — with or without knowing it — that the opportunity cost to simply find new information or technology providers seems to far outweigh any perceived offense on their part. Google’s legal and PR representatives know this. They took great care to frame the recent changes as matters of convenience, simplicity, and security, rather than in more complex and realistic terms.

Making the new policy easy to read was not their only motivation. Though Google posted many on-screen notices, and even sent a mass email to all their users (a rare occurrence), the changes took many by surprise. More importantly, for those users who bothered to read the information made public about the change, Google only made available a brief overview of the policy, in layman’s terms, and a revised FAQ page — the actual terms and conditions were not linked from those pages, and were scarcely to be seen upon further inquiry. Once acquired, though, these new terms reveal a curious shift in the way that Google will manage their relationship and responsibility towards their users. The shift — which deals with slippery phrases and ideas, such as identity and information — effectively both strips users of control over what happens to their digital footprints, and hides that control in Google’s prerogative to maintain a vast, persistent, and deeply centralized set of records. Since only Google can benefit from those records, and only users can be harmed by their use and abuse, the new policy can seem to value privacy only when Google’s corporate interests are in question. So we enter the late stages of a technology monopoly’s rise: their consolidation of control over their users’ decision-making.

Turning to specific issues in the new policy, we find a less obvious, but no less serious conundrum. It arises in the unexpected distinction between what counts for data, as opposed to information.

content vs information. sensitive personal info

content vs data. user uploaded content

what counts for which where determines what is sold and what is kept hidden. what is kept hidden is not deleted including server and search logs by ip addresss.

On Privacy Policies

Effective 1 March 2012, Google adjusted the terms of its privacy policy, affecting users of all its applications. There was no option to waive or deny these changes, aside from cancelling one’s accounts, which would still require the migration and/or deletion of emails, documents, and personally identifying information from Google’s servers. Further, the policy became homogenous across every service and product that Google offers. These were not unprecedented changes, as many End User License Agreements and other similar contracts assume that use of a product or service constitutes unmitigated acceptance of the provider’s terms. But this round of legalese brings two unique changes to discussions of privacy and openness. Ongoing lawsuits against Google (among other large technology providers) highlight the stakes of these discussions. Many of us are so deeply invested in the daily use of Google’s products and services — with or without knowing it — that the opportunity cost to simply find new information or technology providers seems to far outweigh any perceived offense on their part. Google’s legal and PR representatives know this. They took great care to frame the recent changes as matters of convenience, simplicity, and security, rather than in more complex and realistic terms.

Making the policy easy to read was not their only motivation. Though Google posted many on-screen notices, and even sent a mass email to all their users (a rare occurrence), the changes took many by surprise. More importantly, for those users who bothered to read the information made public about the change, Google only made available a brief overview of the policy, in layman’s terms, and a revised FAQ page — the actual terms and conditions were not linked from those pages, and were scarcely to be seen upon further inquiry. Once acquired, though, these terms reveal a curious shift in the way that Google will manage their relationship and responsibility towards their users. The shift — which deals with slippery phrases and ideas, such as identity and information — effectively both strips users of control over what happens to their digital footprints, and hides that control in Google’s prerogative to maintain a vast, persistent, and deeply centralized set of records. Since only Google can benefit from those records, and only users can be harmed by their use and abuse, the policy can seem to value privacy only when Google’s corporate interests are in question. So we enter the late stages of a technology monopoly’s rise: their consolidation of control over their users’ decision-making.

Turning to specific issues in the policy, we find a less obvious, but no less serious conundrum. It arises in the unexpected distinction between what counts for data, as opposed to information.

content vs information. sensitive personal info

content vs data. user uploaded content

what counts for which where determines what is sold and what is kept hidden. what is kept hidden is not deleted including server and search logs by ip addresss.

Internet – on Waste

A simple question sometimes opens unexpected complications. In this case, what counts for the garbage of the internet?

(tl;dr: It can be tempting to swerve into digressions here about wastes of time or wastes of attention a la cat videos. Sorry – instead, this post focuses instead on the production, distribution, circulation, use and deprecation of those media artifacts, their platforms, and the machines on which we view them.)

One way to approach the question is to ask how we measure the energy efficiency of the internet. The factors that influence that measurement include the rate of electricity consumed by mobile devices and their chargers, personal computers, modems and routers, servers, and data centers. Most significantly, the energy required to cool those machines can stagger the mind. A proper study of this use must also account for the amount of energy invested in the production of the same machines. Efficient consumption of resources serves the interests of the largest discrete consumers and of the utility providers who make the resources available to aggregate consumers, but without discriminating between economic and ecological criteria. For example, GreenPeace’s recent “Dirty Data” report, which embroiled Facebook and other companies in P.R. and legal battles, argues that large IT firms, especially data centers, continue to consume energy in 19th- and 20th- century industrial factory patterns, rather than embracing “clean” energy as wholeheartedly as efficiency. While new facilities constructed over the past few years by Apple, Google, Amazon, and Microsoft certainly deserve their accolades for efficient design. Efficiency, however, only provides one lens onto the original question of garbage or waste. Continue reading

Internet – Geography, and Africa Introduced

We expect no clean equivalence between infrastructure, labor, capital, and internet development. Still, we know that the growth of a robust modern internet takes vast amounts of time, skilled labor, and knowledge — all elements of advanced capital. So, when we consider the rise of today’s African internet, we must ask, first, who builds it — and then, where its infrastructure overlaps or clashes with existing geographical patterns. Heavily visual organization and logic help think through these issues of backbone, traffic, and investment. Their combination leads to some interesting insight to the specific challenges facing the continuation of Africa’s internet-building. Continue reading

Internet – On the Markets

We turn now from contextual summaries of broad topics to more specific analyses of focused problems. The case in point this week is the curious interplay of market and economic themes in discourses and studies of the internet. There are several fascinating phenomena associated with the rise of the internet as a platform for trade as well as communication and computation. These, however, have roots that run deeper than their own emergence, in the economic and historical conditions that undergird the internet’s development. As trade and commerce proliferate online, they mimic (at least at first) the structure and behavior of their non-internet predecessors, which themselves must shift or extend their positions to accomodate this competition. As internet markets continue to grow and find their own forms, their effects on their non-internetted counterparts deepens. And as financial instruments and economic models become more closely attuned to internet machinations, it becomes easier – from a cultural or social standpoint – to overlook the most obvious historical and global correlations to this situation.

A silly image for a spammy post on webtech-team.com

Internet – On the Histories

This series digresses here to review and consider internet history. This includes, of course, the well-documented series of events and interactions and innovations and and and … that led to what we see when we go online these days. It also includes the conditions under which those events and interactions and innovations and so on took place, to inform ongoing research into internet development in other parts of the contemporary world. And, these posts stemming from the skeptical position of cultural scholarship, it also questions who gets to write the history of the internet, and with what sources. This line of questioning leads us back, cautiously, to the major themes of the semester.

Internet – Technical Literature

Internet – Introduction

For all its familiarity to users on a daily basis, the internet remains a strange and wild beast, full of secrets and surprises for those of us who take it as our object of research. This marks the first entry in a weekly series of short essays, reflecting on my independent reading this semester with Dr. Sharon Leon, on the topic of the internet in cultural perspective. This week, I will lay out the key terms, concepts, and questions for our course of study, and note the work plan for the semester by way of conclusion. Over this semester, I hope to learn not only myriad technical details and interesting anecdotes about the internet, but also how a rigorously cultural approach to its study might inform my own and others’ future research. These essays should serve to keep the research regular, progressive, and grounded: the best technique that I know for tackling large and complex problems is patience and determination.

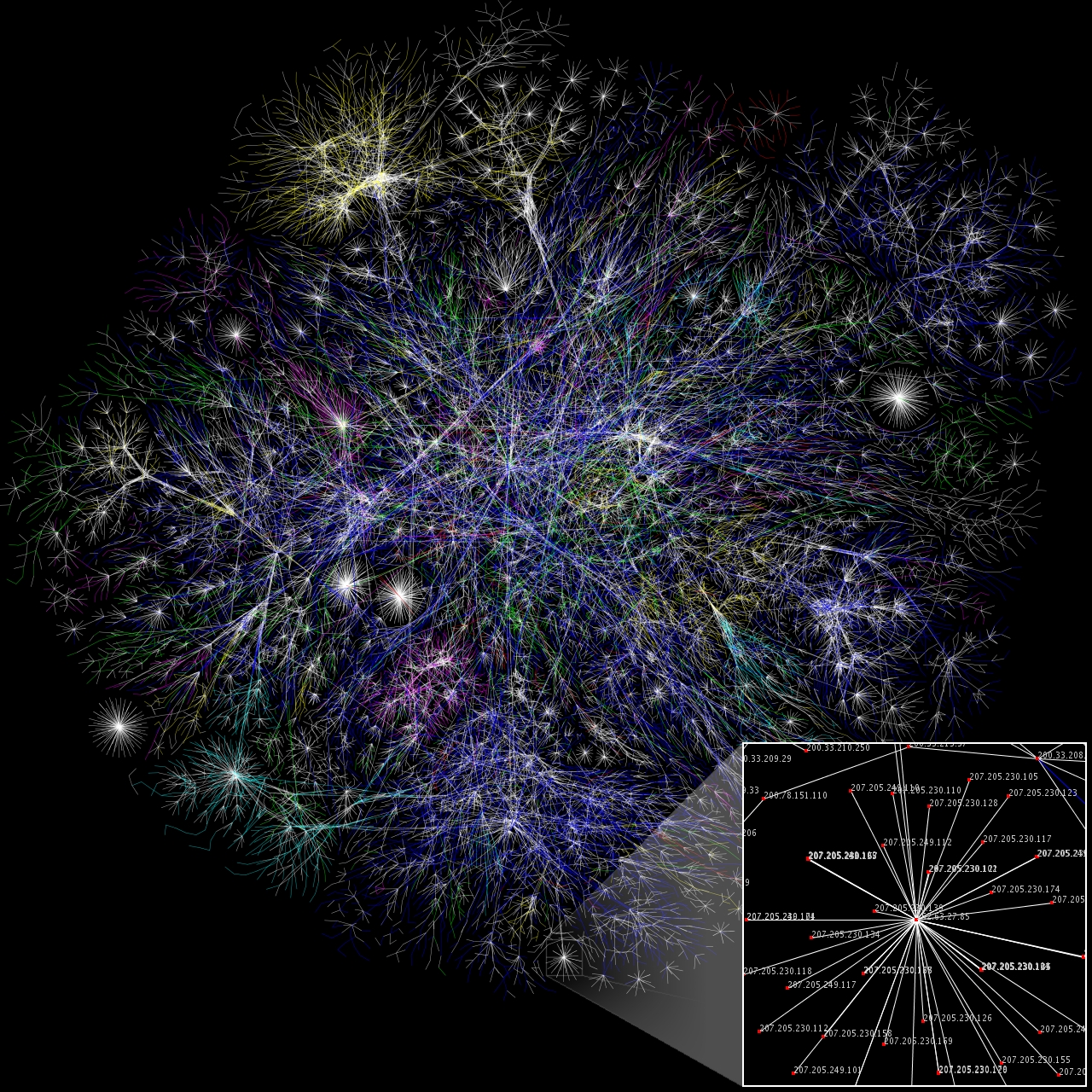

For this week, I reviewed some technical literature on the definition, statistical character, and high-level architecture of the internet. These came from academic, market research, and non-profit sources. The wealth of data available now – an archive stretching back at least through the early 1990s – provides some clear background. The internet today comprises some dozen layers from physical infrastructure through end users, and encompasses some untold trillions of web pages, links, and networks. Of course, the most important key terms that this week’s readings reinforced were the obvious ones:

- Networks – the baseline units of which the internet is made up. Comprised of public and private, virtual and physical, metaphorical and concrete, networks are the touchstone and the cornerstone of both the idea and the artifact of the internet. We define networks for our purposes as sets of connected agents – machine, human, or virtual – and include in the set the connections themselves.

- Communication – When we define the internet, we encounter conflicts between those (e.g. the FCC) who wish to define it as a communications medium akin to telephony or broadcast television, and those who seek another primary definition (e.g. the FTC, who wishes to define it as a commerce and trade platform like the stock market, or others who believe that it constitutes a public utility like the power grid or water supply lines). For our purposes, we can remain comfortable with a complex and often contradictory definition that accounts for different structural, economic, and cultural deployments of the internet. This is because we will define it primarily as a CONCEPT, and only secondarily as an ARTIFACT.

- Medium/Media – Regardless of the legal or formal definition of the internet, its status as a communications medium is hardly in doubt. In practice “new media” has folded largely into the internet – digital communications, human-computer interaction, and computer-mediated-communication included alongside applications such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, email, and the like. We use media in the broadest possible sense, then, following McLuhan’s prescient if aphoristic sensibility most of the time.

- Structure and Infrastructure – The first few weeks of this course will dedicate their time to unpacking and making clear the incredible complexity at work in the background of any internet instance. The most important aspects of structure and infrastructure, from a beginner’s standpoint, are layers, links, protocols, platforms applications, and services. We will define these in more detail next week.

- Other terms to be defined next week: community, commodity, and architecture.

The key questions for this week are the overall questions for the course. When we define “the internet,” two specific parts of that definition resonate for our purposes. First, what is unique about the internet as a cultural object? Second, what does a cultural study of the internet entail? These lead to our historical inquiries: how did the internet as we know it develop, what kinds of labor were involved, and how has its cultural significance changed over time? We also encounter architectural questions of culture: who maintains and manages each layer, who composes and follows each protocol, and to what ends? Placing the object in social and political context, we will ask whose interests the internet has and continues to serve, and what the mutual effects are between its structure and its context. Finally, diving into the questions of cultural significance, we will examine the internet’s political, economic, and subjective impacts – or at least plan how to answer those. For the next week, however, we will focus on a specific question: What is the structure of the internet? By the time we ask how it got that way, we will have entered the historical aspects of our investigation.

- This is perhaps the most popular visualization of the internet.