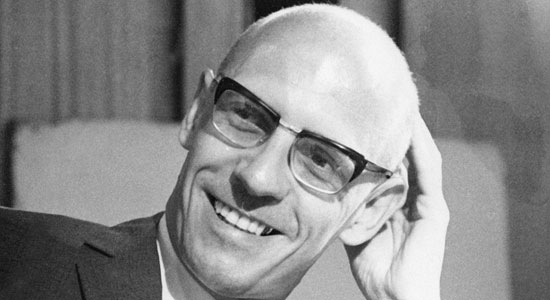

A landmark topical study from Foucault’s early career, History of Madness took nearly forty years before arriving in the U.S. in a full translation. Jean Khalfa’s magnificent treatment of the sprawling text delivers Anglophone readers more than just extra pages. The differences between Madness and Civilization (based on the 1964 adaptation) and History of Madness (based on the original 1961 version) extend to conceptual nuances as well. In particular, the abridgment of the critique of psychiatry, in Madness and Civilization, flirts with a characterization of madness as repressed genius. But the more detailed argumentation in History of Madness, especially its focus on the institutional disciplines surrounding reason, emphasizes a conscientiously empirical archaeology of reason instead. Still, a central lament, for the loss of unreason after the 18th century, remains in force across both texts. Continue reading

Tag Archives: review

Foucault – Archeology of Knowledge

Foucault’s methodological treatise, a decade in the writing, dismantles and reassembles historiography and epistemology. Rather than treat its object — discourse — as evidence of contiguous historical phenomena, Archaeology of Knowledge (AK) situates discourse as the rules that govern our organization and understanding of historical (as well as political, social, and other sets of) knowledge. At the same time, it describes discourse as a practice that encompasses the very making of those rules. True, then, that this abbreviated forum, as always, would fall short of adequate recapitulation of the book’s themes, let alone to float critique. But we can try:

The frontiers of a book are never clear-cut: beyond the title, the first lines, and the last full stop, beyond its internal configuration and its autonomous form, it is caught up in a system of references to other books, other texts, other sentences: it is a node within a network. Continue reading

Foucault – Position – Epistemic Limits

Whether coursing through archival data or meditating on turns of language, Foucault’s early works — the History of Madness, the Birth of the Clinic, the Order of Things, and the Archaeology of Knowledge — each address ways of knowing how and what we think. Based on the approach in those works, we can refocus their efforts onto a tertiary question. While lacking the familiar modulus of power, this approach can still maintain a close attention to the thought of thought as such. It helps elucidate how we conceive of the conditions to this reflexive thought, and thereby to sketch contemporary epistemic limitations. The motivating impulse here, then, is: What exists outside our conditions of possibility of thought, and how can we know it? Continue reading