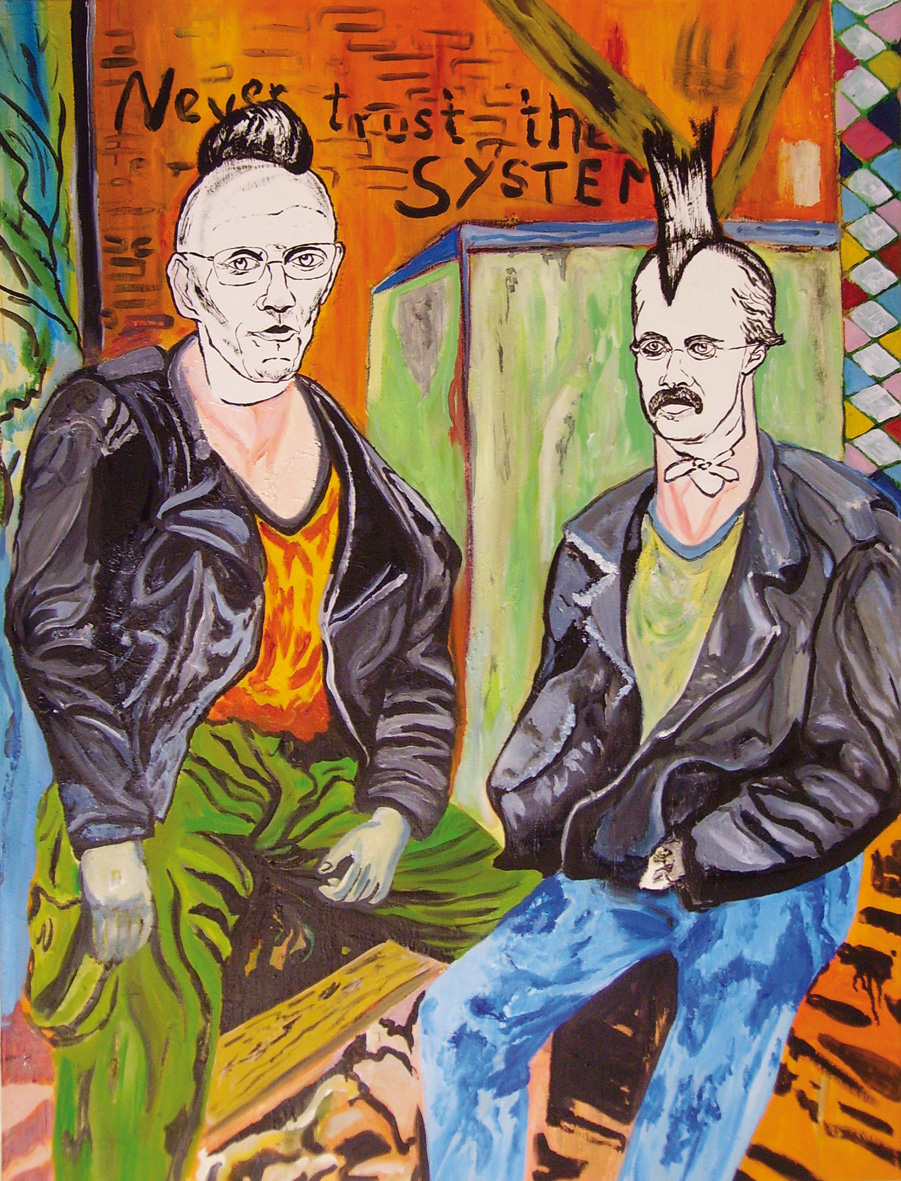

“Genealogy… must expose a body totally inscribed by history, and history’s destruction of the body.” (my translation)

Tag Archives: archaeology

Foucault – Birth of the Clinic

Foucault’s second major publication follows the immense History of Madness, and precedes The Order of Things. Its focus on the medical gaze, and on the epistemic shift concurrent with the turn of the 18th century, emphasizes the themes that carry between those two texts. Staunchly archaeological, The Birth of the Clinic traces the moduli of language as evidence and archive, entryways into the probing questions of medical practice and assumption throughout the period. Remarkably, throughout this subtle and sensitive critique of a scientific logic that insists upon the technical objectivity of images and words of the body, Foucault’s own treatment of the body – as historically and socially embedded – avoids direct confrontation with the conditions of possible embodiment of the medical regard itself.

Internet – Lit Reviews – Chun, Nakamura, Gitelman

Three writers who focus on the use and rhetoric of media, rather than on their inherent characteristics or their ethical valences, come together here. Wendy H. K. Chun demands that our attention to the social contexts of emergent technologies center on the political matters of force and sovereignty. Lisa Nakamura draws our attention to myriad, and structural, irruptions of old inequalities as manifested in ostensibly transcendent new media. And Lisa Gitelman pointedly reminds us, through a meticulous and engaging historiography, that what we call ‘new’ in media has older histories than we often care to admit, that all media were new once, and that any divergent practice or technology enters a complex set of other, perhaps related, media, in which nothing can be outgrown, only deprecated. Together, these thinkers provide good scholarship on which further research can be modelled, and provocative questions that demand further thought.

Continue reading

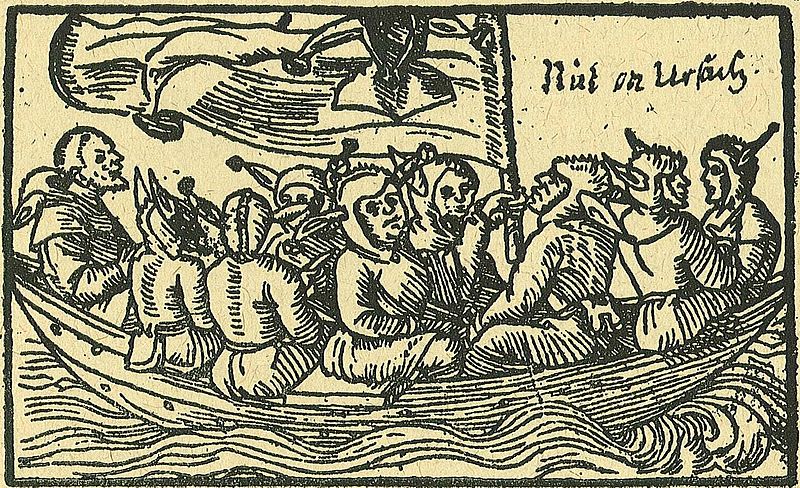

Foucault – History of Madness / Madness and Civilization

A landmark topical study from Foucault’s early career, History of Madness took nearly forty years before arriving in the U.S. in a full translation. Jean Khalfa’s magnificent treatment of the sprawling text delivers Anglophone readers more than just extra pages. The differences between Madness and Civilization (based on the 1964 adaptation) and History of Madness (based on the original 1961 version) extend to conceptual nuances as well. In particular, the abridgment of the critique of psychiatry, in Madness and Civilization, flirts with a characterization of madness as repressed genius. But the more detailed argumentation in History of Madness, especially its focus on the institutional disciplines surrounding reason, emphasizes a conscientiously empirical archaeology of reason instead. Still, a central lament, for the loss of unreason after the 18th century, remains in force across both texts. Continue reading

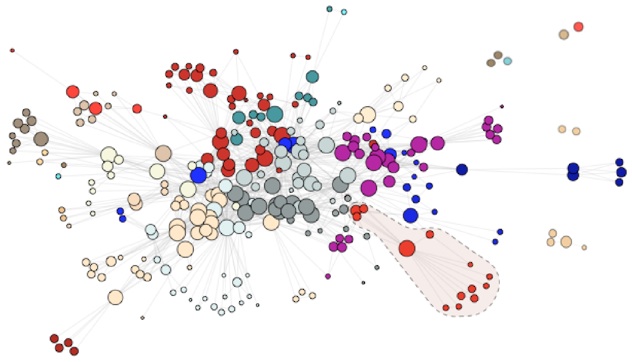

Foucault – Archeology of Knowledge

Foucault’s methodological treatise, a decade in the writing, dismantles and reassembles historiography and epistemology. Rather than treat its object — discourse — as evidence of contiguous historical phenomena, Archaeology of Knowledge (AK) situates discourse as the rules that govern our organization and understanding of historical (as well as political, social, and other sets of) knowledge. At the same time, it describes discourse as a practice that encompasses the very making of those rules. True, then, that this abbreviated forum, as always, would fall short of adequate recapitulation of the book’s themes, let alone to float critique. But we can try:

The frontiers of a book are never clear-cut: beyond the title, the first lines, and the last full stop, beyond its internal configuration and its autonomous form, it is caught up in a system of references to other books, other texts, other sentences: it is a node within a network. Continue reading

Foucault – Order of Things

We have no words for things. Rather, words are things that make other things. Concatenated discourses — words in their material aggregation — actively shape more than signification and syntax. Foucault’s principal argument throughout The Order of Things attacks the commonsense notion that words merely represent, or that mimetic functions are language’s sad destiny as medium of communication, after we enter epistemic formations of knowledge that structure such notions. Granting deeper, nigh on originary, primacy to language, as progenitor of ways of being and of making things in the world, he shows us how such a notion arose in shifts between Western historical eras: the Renaissance, Classical, and modern periods. Continue reading