Author Archives: lewis

Internet – Synthesis – Methods and Approaches

While composing the preliminary reviews of literature that surround this post (it being posted retrospectively – something pops up here about the instability of blog-time, no doubt) certain tendencies and distinctions among the many approaches to internet studies have cemented. As the time comes to distinguish my own approach and its component pieces from the existing ones, both those which contribute to it and those from which it makes more sense to distance ourselves, a synthesis of those reviews comes into form. Tracing those groups in the literature that hang together, marking the details and purposes and focus of the ongoing project, and then arguing for the validity of a fresh approach and method, this post will form a temporary holding point en route to the field statement’s proposal and procedure. But we begin just by restating the themes of the semester so far.

Continue reading

Notes on the Undertaking

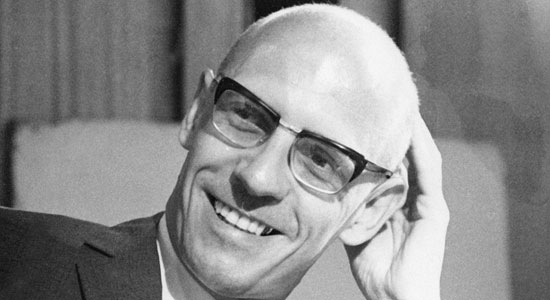

What is a dead man to a reputation?

After all, the focus of a study of or so deeply involving MF cannot but deride itself when falsifying history for sake of hagiography. Anyway, no one who reads this (Dr. Albanese?) can excuse, apologize, deflect the certain absence of political upheaval in modern academics. Our campuses are designed straitjackets – no riots for us, nor occuptions of administrative buildings. So when our collective sensibilities are offended, who speaks for disenfranchised privileged paradoxes? Ours is for impotence. Our writing stifles itself every chance it gets, in obscurity and in loops of logic. We cannot even concentrate, as a group, on critical issues, critical theory, critical thought, without the distraction of a million meetings and emails. This is no paean to a lost romantic teleology of scholarship. I find the distrust of the internet-as-archive distasteful, facile, impotence on impotence. Simply put, its statements require a different grammar. Its interpretability as a corpus requires the logic of Google — as far as indexing and ordering goes — rather than the logic of Derrida. But what bothers me is the thesis that these logics are incommensurable. This problem has already been solved — and not by appeal to superficial empiricism or false positivism, either. No, our emphasis remains on reading Foucault for what we can learn about how to learn about our world, on- and offline, abstract and concrete. Our realms and regimes of discourse have shifted yet again. To engage archaeology — “of” media, technology, the like — deposes critique, and no mistake. So we turn to genealogy, not in a vain attempt to recover an essential Foucault (such a book would never rise above glib punchlines and observational interpretation) but precisely in an attempt to articulate an inessential Foucault.

Continue reading

Internet – Bibliography

Internet Studies – Bibliography

Foucault – History of Madness / Madness and Civilization

A landmark topical study from Foucault’s early career, History of Madness took nearly forty years before arriving in the U.S. in a full translation. Jean Khalfa’s magnificent treatment of the sprawling text delivers Anglophone readers more than just extra pages. The differences between Madness and Civilization (based on the 1964 adaptation) and History of Madness (based on the original 1961 version) extend to conceptual nuances as well. In particular, the abridgment of the critique of psychiatry, in Madness and Civilization, flirts with a characterization of madness as repressed genius. But the more detailed argumentation in History of Madness, especially its focus on the institutional disciplines surrounding reason, emphasizes a conscientiously empirical archaeology of reason instead. Still, a central lament, for the loss of unreason after the 18th century, remains in force across both texts. Continue reading

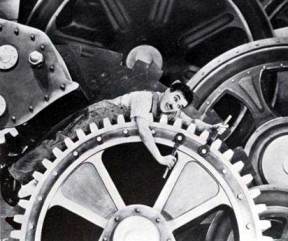

Internet – on Labor

At a relaxed dinner with a good friend recently, we discussed the difficulty of finding a job in Detroit over the last few years. We spoke about the population’s available, marketable skills, and compared the price of land/rent to the type of organizations with the capital to buy it up. Then, we touched on a curious potential outcome of the current grim circumstances. In ten or fifteen years, we posited, when the city has grown again and its workforce is active again, a primary economic driver could well be the Silicone titans. This unusual placement of internet-driven internet drivers would seem out of place in the Motor City, except for a few key factors. First, technology industries require massive investments of capital for infrastructure and of labor for support in addition to the engineers and designers who are their most visible participants. Second, the data in the United States flows through Detroit, necessitating more of those support staff as that stream grows. And finally, the low cost of land and utilities, and the propensity of large IT firms to model their operations on 19th and 20th century factories, means that the companies have incentive to move to such an area already. Some small moves in this direction could trigger large changes to the economic situation there. Continue reading

Foucault – Archeology of Knowledge

Foucault’s methodological treatise, a decade in the writing, dismantles and reassembles historiography and epistemology. Rather than treat its object — discourse — as evidence of contiguous historical phenomena, Archaeology of Knowledge (AK) situates discourse as the rules that govern our organization and understanding of historical (as well as political, social, and other sets of) knowledge. At the same time, it describes discourse as a practice that encompasses the very making of those rules. True, then, that this abbreviated forum, as always, would fall short of adequate recapitulation of the book’s themes, let alone to float critique. But we can try:

The frontiers of a book are never clear-cut: beyond the title, the first lines, and the last full stop, beyond its internal configuration and its autonomous form, it is caught up in a system of references to other books, other texts, other sentences: it is a node within a network. Continue reading

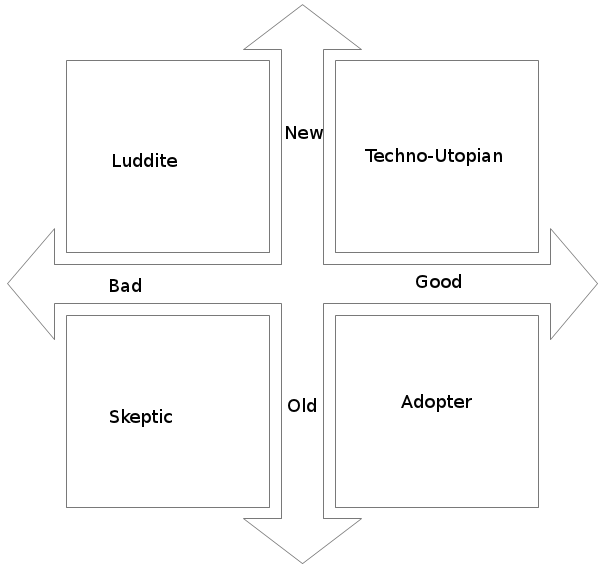

Internet – Synthesis – On Newness

The question of what, after all, is so new about the internet has run through the introductory and summary posts in this series. It is a divisive question. Some proclaim the revolutionary, worldchanging emergence of the internet a wholly unique phenomenon. Others describe its continuity with older forms of media, communication, technology, or ideas. And each vein has its proponents and detractors of the internet’s cultural effects, which seem ubiquitously manifest, though not unequivocally ethically or morally valenced. Since we are concerned, here, with not just cultural effects but also cultural conditions for today’s internet, though, we cannot neatly reduce our approach to any of these positions.

So, we are faced with a series of comparisons and contrasts.

On Privacy Policies

Effective 1 March 2012, Google adjusted the terms of its privacy policy, affecting users of all its applications. There was no option to waive or deny these changes, aside from cancelling one’s accounts, which would still require the migration and/or deletion of emails, documents, and personally identifying information from Google’s servers. Further, the policy became homogenous across every service and product that Google offers. These were not unprecedented changes, as many End User License Agreements and other similar contracts assume that use of a product or service constitutes unmitigated acceptance of the provider’s terms. But this round of legalese brings two unique changes to discussions of privacy and openness. Ongoing lawsuits against Google (among other large technology providers) highlight the stakes of these discussions. Many of us are so deeply invested in the daily use of Google’s products and services — with or without knowing it — that the opportunity cost to simply find new information or technology providers seems to far outweigh any perceived offense on their part. Google’s legal and PR representatives know this. They took great care to frame the recent changes as matters of convenience, simplicity, and security, rather than in more complex and realistic terms.

Making the policy easy to read was not their only motivation. Though Google posted many on-screen notices, and even sent a mass email to all their users (a rare occurrence), the changes took many by surprise. More importantly, for those users who bothered to read the information made public about the change, Google only made available a brief overview of the policy, in layman’s terms, and a revised FAQ page — the actual terms and conditions were not linked from those pages, and were scarcely to be seen upon further inquiry. Once acquired, though, these terms reveal a curious shift in the way that Google will manage their relationship and responsibility towards their users. The shift — which deals with slippery phrases and ideas, such as identity and information — effectively both strips users of control over what happens to their digital footprints, and hides that control in Google’s prerogative to maintain a vast, persistent, and deeply centralized set of records. Since only Google can benefit from those records, and only users can be harmed by their use and abuse, the policy can seem to value privacy only when Google’s corporate interests are in question. So we enter the late stages of a technology monopoly’s rise: their consolidation of control over their users’ decision-making.

Turning to specific issues in the policy, we find a less obvious, but no less serious conundrum. It arises in the unexpected distinction between what counts for data, as opposed to information.

content vs information. sensitive personal info

content vs data. user uploaded content

what counts for which where determines what is sold and what is kept hidden. what is kept hidden is not deleted including server and search logs by ip addresss.

On Google’s Privacy Policy

Effective 1 March 2012, Google adjusted the terms of its privacy policy, affecting users of all its applications. There was no option to waive or deny these changes, aside from cancelling one’s accounts, which would still require the migration and/or deletion of emails, documents, and personally identifying information from Google’s servers. Further, the policy became homogenous across every service and product that Google offers. These were not unprecedented changes, as many End User License Agreements and other similar contracts assume that use of a product or service constitutes unmitigated acceptance of the provider’s terms. But this round of legalese brings two unique changes to discussions of privacy and openness. Ongoing lawsuits against Google (among other large technology providers) highlight the stakes of thses discussions. Many of us are so deeply invested in the daily use of Google’s products and services — with or without knowing it — that the opportunity cost to simply find new information or technology providers seems to far outweigh any perceived offense on their part. Google’s legal and PR representatives know this. They took great care to frame the recent changes as matters of convenience, simplicity, and security, rather than in more complex and realistic terms.

Making the new policy easy to read was not their only motivation. Though Google posted many on-screen notices, and even sent a mass email to all their users (a rare occurrence), the changes took many by surprise. More importantly, for those users who bothered to read the information made public about the change, Google only made available a brief overview of the policy, in layman’s terms, and a revised FAQ page — the actual terms and conditions were not linked from those pages, and were scarcely to be seen upon further inquiry. Once acquired, though, these new terms reveal a curious shift in the way that Google will manage their relationship and responsibility towards their users. The shift — which deals with slippery phrases and ideas, such as identity and information — effectively both strips users of control over what happens to their digital footprints, and hides that control in Google’s prerogative to maintain a vast, persistent, and deeply centralized set of records. Since only Google can benefit from those records, and only users can be harmed by their use and abuse, the new policy can seem to value privacy only when Google’s corporate interests are in question. So we enter the late stages of a technology monopoly’s rise: their consolidation of control over their users’ decision-making.

Turning to specific issues in the new policy, we find a less obvious, but no less serious conundrum. It arises in the unexpected distinction between what counts for data, as opposed to information.

content vs information. sensitive personal info

content vs data. user uploaded content

what counts for which where determines what is sold and what is kept hidden. what is kept hidden is not deleted including server and search logs by ip addresss.