Whether coursing through archival data or meditating on turns of language, Foucault’s early works — the History of Madness, the Birth of the Clinic, the Order of Things, and the Archaeology of Knowledge — each address ways of knowing how and what we think. Based on the approach in those works, we can refocus their efforts onto a tertiary question. While lacking the familiar modulus of power, this approach can still maintain a close attention to the thought of thought as such. It helps elucidate how we conceive of the conditions to this reflexive thought, and thereby to sketch contemporary epistemic limitations. The motivating impulse here, then, is: What exists outside our conditions of possibility of thought, and how can we know it? Continue reading

Author Archives: lewis

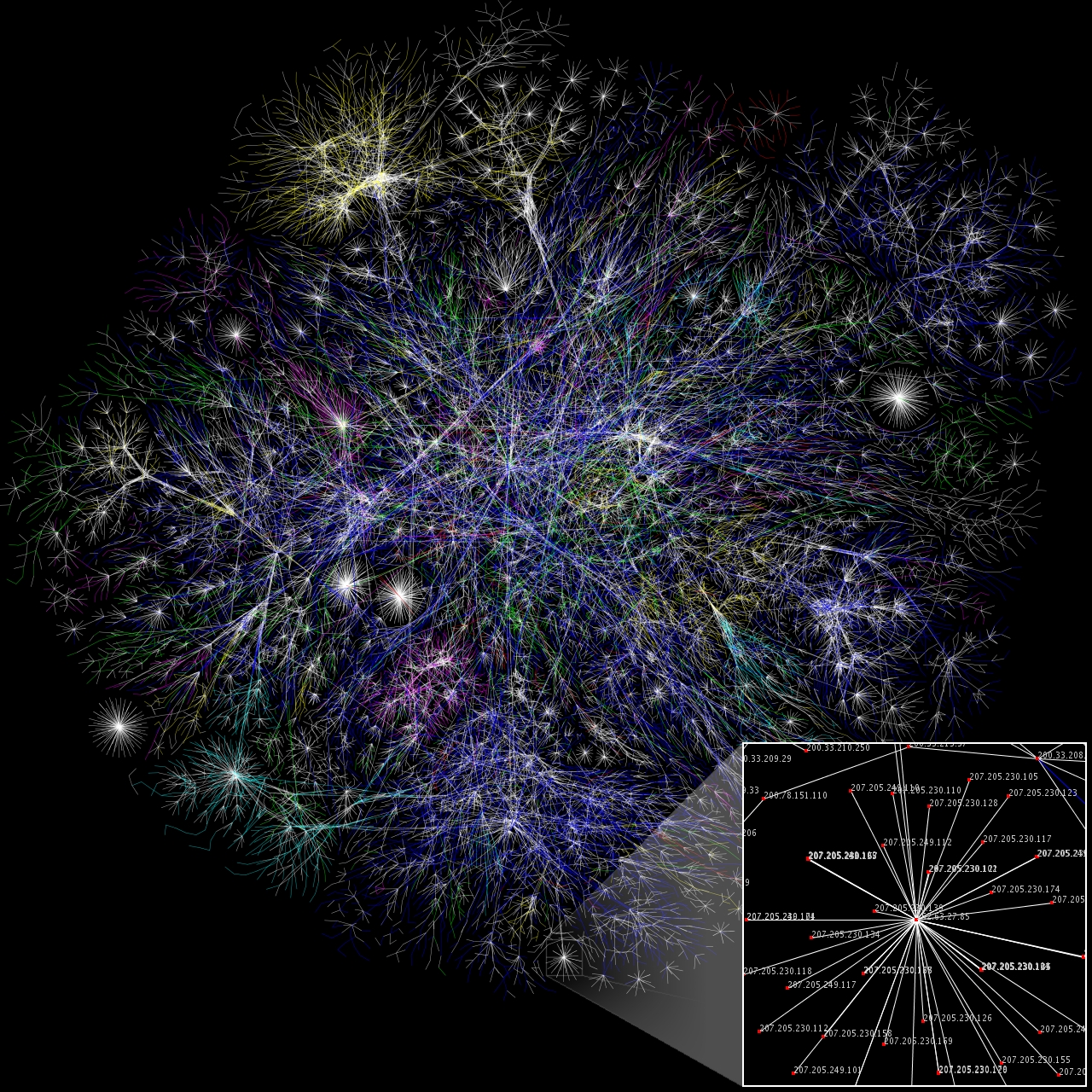

Internet – on Waste

A simple question sometimes opens unexpected complications. In this case, what counts for the garbage of the internet?

(tl;dr: It can be tempting to swerve into digressions here about wastes of time or wastes of attention a la cat videos. Sorry – instead, this post focuses instead on the production, distribution, circulation, use and deprecation of those media artifacts, their platforms, and the machines on which we view them.)

One way to approach the question is to ask how we measure the energy efficiency of the internet. The factors that influence that measurement include the rate of electricity consumed by mobile devices and their chargers, personal computers, modems and routers, servers, and data centers. Most significantly, the energy required to cool those machines can stagger the mind. A proper study of this use must also account for the amount of energy invested in the production of the same machines. Efficient consumption of resources serves the interests of the largest discrete consumers and of the utility providers who make the resources available to aggregate consumers, but without discriminating between economic and ecological criteria. For example, GreenPeace’s recent “Dirty Data” report, which embroiled Facebook and other companies in P.R. and legal battles, argues that large IT firms, especially data centers, continue to consume energy in 19th- and 20th- century industrial factory patterns, rather than embracing “clean” energy as wholeheartedly as efficiency. While new facilities constructed over the past few years by Apple, Google, Amazon, and Microsoft certainly deserve their accolades for efficient design. Efficiency, however, only provides one lens onto the original question of garbage or waste. Continue reading

Internet – Geography, and Africa Introduced

We expect no clean equivalence between infrastructure, labor, capital, and internet development. Still, we know that the growth of a robust modern internet takes vast amounts of time, skilled labor, and knowledge — all elements of advanced capital. So, when we consider the rise of today’s African internet, we must ask, first, who builds it — and then, where its infrastructure overlaps or clashes with existing geographical patterns. Heavily visual organization and logic help think through these issues of backbone, traffic, and investment. Their combination leads to some interesting insight to the specific challenges facing the continuation of Africa’s internet-building. Continue reading

Internet – On the Markets

We turn now from contextual summaries of broad topics to more specific analyses of focused problems. The case in point this week is the curious interplay of market and economic themes in discourses and studies of the internet. There are several fascinating phenomena associated with the rise of the internet as a platform for trade as well as communication and computation. These, however, have roots that run deeper than their own emergence, in the economic and historical conditions that undergird the internet’s development. As trade and commerce proliferate online, they mimic (at least at first) the structure and behavior of their non-internet predecessors, which themselves must shift or extend their positions to accomodate this competition. As internet markets continue to grow and find their own forms, their effects on their non-internetted counterparts deepens. And as financial instruments and economic models become more closely attuned to internet machinations, it becomes easier – from a cultural or social standpoint – to overlook the most obvious historical and global correlations to this situation.

A silly image for a spammy post on webtech-team.com

Internet – On the Histories

This series digresses here to review and consider internet history. This includes, of course, the well-documented series of events and interactions and innovations and and and … that led to what we see when we go online these days. It also includes the conditions under which those events and interactions and innovations and so on took place, to inform ongoing research into internet development in other parts of the contemporary world. And, these posts stemming from the skeptical position of cultural scholarship, it also questions who gets to write the history of the internet, and with what sources. This line of questioning leads us back, cautiously, to the major themes of the semester.

Foucault – Order of Things

We have no words for things. Rather, words are things that make other things. Concatenated discourses — words in their material aggregation — actively shape more than signification and syntax. Foucault’s principal argument throughout The Order of Things attacks the commonsense notion that words merely represent, or that mimetic functions are language’s sad destiny as medium of communication, after we enter epistemic formations of knowledge that structure such notions. Granting deeper, nigh on originary, primacy to language, as progenitor of ways of being and of making things in the world, he shows us how such a notion arose in shifts between Western historical eras: the Renaissance, Classical, and modern periods. Continue reading

Foucault – Key Concepts – Archaeology

Foucault

These weeks I’ve turned from biographical and summary readings to Foucault’s early works. From here on, these posts will proceed at conceptual levels as much as is possible. Today, we turn to archaeology. In its simplest reduction, the concept denotes a history of discourse. In books such as the History of Madness, the Archaeology of Knowledge, and the Order of Things, Foucault undertakes examinations of discursive formations ranging from health and madness to scientific understanding to aesthetics and perception. Throughout each of these, he frames the conditions of knowledge in a given time period as constrained by the characteristics of that period, a general way of organizing and thinking about the world in each that he names an episteme. So, archaeology is the study of “epistemae,” and an episteme places discourse in historical context.

Internet – Technical Literature

Foucault – Tutor-Texts and Intellectual Lineage

This first post in a short-term regular series of essays on Michel Foucault deals with his most famous influences. I begin with the precursors to Foucault’s own production of knowledge because their work and tutelage form the conditions of that production. This requires that I oversimplify some of their contributions to cultural scholarship and critical theory. I hope to maintain a baseline level of respect for their importance without fetishizing their names, just as I intend to maintain the tension between the familiarity of Foucault’s own name and the irreducibility of his intellectual production to any single certain thought or text. Enough lingering on qualifications and breast-beating, then. Let me turn to the names and their significance for Foucault’s emergence as a theoretical producer – and event.

- Michel Foucault – image via Creative Commons.

Internet – Introduction

For all its familiarity to users on a daily basis, the internet remains a strange and wild beast, full of secrets and surprises for those of us who take it as our object of research. This marks the first entry in a weekly series of short essays, reflecting on my independent reading this semester with Dr. Sharon Leon, on the topic of the internet in cultural perspective. This week, I will lay out the key terms, concepts, and questions for our course of study, and note the work plan for the semester by way of conclusion. Over this semester, I hope to learn not only myriad technical details and interesting anecdotes about the internet, but also how a rigorously cultural approach to its study might inform my own and others’ future research. These essays should serve to keep the research regular, progressive, and grounded: the best technique that I know for tackling large and complex problems is patience and determination.

For this week, I reviewed some technical literature on the definition, statistical character, and high-level architecture of the internet. These came from academic, market research, and non-profit sources. The wealth of data available now – an archive stretching back at least through the early 1990s – provides some clear background. The internet today comprises some dozen layers from physical infrastructure through end users, and encompasses some untold trillions of web pages, links, and networks. Of course, the most important key terms that this week’s readings reinforced were the obvious ones:

- Networks – the baseline units of which the internet is made up. Comprised of public and private, virtual and physical, metaphorical and concrete, networks are the touchstone and the cornerstone of both the idea and the artifact of the internet. We define networks for our purposes as sets of connected agents – machine, human, or virtual – and include in the set the connections themselves.

- Communication – When we define the internet, we encounter conflicts between those (e.g. the FCC) who wish to define it as a communications medium akin to telephony or broadcast television, and those who seek another primary definition (e.g. the FTC, who wishes to define it as a commerce and trade platform like the stock market, or others who believe that it constitutes a public utility like the power grid or water supply lines). For our purposes, we can remain comfortable with a complex and often contradictory definition that accounts for different structural, economic, and cultural deployments of the internet. This is because we will define it primarily as a CONCEPT, and only secondarily as an ARTIFACT.

- Medium/Media – Regardless of the legal or formal definition of the internet, its status as a communications medium is hardly in doubt. In practice “new media” has folded largely into the internet – digital communications, human-computer interaction, and computer-mediated-communication included alongside applications such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, email, and the like. We use media in the broadest possible sense, then, following McLuhan’s prescient if aphoristic sensibility most of the time.

- Structure and Infrastructure – The first few weeks of this course will dedicate their time to unpacking and making clear the incredible complexity at work in the background of any internet instance. The most important aspects of structure and infrastructure, from a beginner’s standpoint, are layers, links, protocols, platforms applications, and services. We will define these in more detail next week.

- Other terms to be defined next week: community, commodity, and architecture.

The key questions for this week are the overall questions for the course. When we define “the internet,” two specific parts of that definition resonate for our purposes. First, what is unique about the internet as a cultural object? Second, what does a cultural study of the internet entail? These lead to our historical inquiries: how did the internet as we know it develop, what kinds of labor were involved, and how has its cultural significance changed over time? We also encounter architectural questions of culture: who maintains and manages each layer, who composes and follows each protocol, and to what ends? Placing the object in social and political context, we will ask whose interests the internet has and continues to serve, and what the mutual effects are between its structure and its context. Finally, diving into the questions of cultural significance, we will examine the internet’s political, economic, and subjective impacts – or at least plan how to answer those. For the next week, however, we will focus on a specific question: What is the structure of the internet? By the time we ask how it got that way, we will have entered the historical aspects of our investigation.

- This is perhaps the most popular visualization of the internet.